Some time back, I wrote a short piece for print publication, and the day after I submitted it received a phone call. The editor questioned my use of the

odd phrase "the Christian Faith and the Catholic Church." Did I intend to use "Christian Faith" in a broader ecumenical sense? Was I attempting to distinguish Christianity in general with the Catholic Church in particular? The editor noted that the article had no apparent ecumenical focus and seemed to be solely dealing with issues related to the Catholic Church itself.

I explained that the Church Fathers often spoke in such terms. My use of the phrase was merely echoing that nomenclature. The editor therefore suggested that I simplify the phrase to reduce possible confusion for the readers. As I explicitly rejected the suggestion to "just go with the Roman Catholic Faith" we eventually agreed on the phrase "the Catholic Church." (It also saved four words!)

C'est la vie!

The discussion brought into clear relief differences in how we often view the Faith and our Church today versus the view of the Fathers. For them, there was but One Church, the Catholic Church, and One Faith, the Christian Faith. The editor interpreted my choice of phrasing in terms of a distinction, a contrast. When the Church Fathers spoke of the Christian Faith

and the Catholic Church they were asserting an essential relationship, not a contrast but an identification. For them, to be a Christian is to be part of the community of Faith, the household of God, the Body of Christ; i.e., the Church. (If there's no such thing as an atheist in a foxhole, we might equally say that to the Church Fathers there's also no such thing as a Christian apart from the Church.)

That the editor, a very well-educated, intellectual professional for whom I have much respect, misunderstood what I considered to be a simple turn of phrase is not surprising. The sometimes-wide gulf between what our Lord requires, what the Gospel proclaims and the Church teaches and what we occasionally see actually happening in the Church is often so striking as to require little comment here. We perceive the ideal and bemoan the reality of human failure to live up to the ideal. And, of course, there is the issue of competing churches, perspectives and interpretations.

Yet, we should reflect on the Fathers' understanding that the relation between the Faith and the Church is of identification and essential connection, not difference and distinction. For the Fathers, to be Christian is to be

in the Church, and to be a member

of the Church is the

sin qua non of whether one

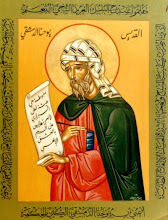

is a Christian. It is an iconic view recognizing the essential truth that the Image can both affirm and be affirmed by the reality of the human condition. The Fathers could squarely face the brutal realities of human weakness, cruelty, sin and corruption while un-hypocritically also affirming the Truth of the Gospel and what it both inspires and requires of us.

Then how did we come to such as state as our contemporary situation in which it seems natural to balance the Faith and the Church as separate or even mutually exclusive realities?

In truth, what seems to have happened is that for some theologians a certain embarrassment arose in the era so quaintly called the Enlightenment. The new focus on man

qua man, later coupled with the industrial revolution's discovery that tools could evolve to such a point as to substantially change the world, led to an evolution in man's self-understanding at once intellectual, moral and metaphysical.

Long held assumptions of human life were shown to be either mistaken or alterable. Comets no longer need be feared as harbingers of God's wrath (although we have now substituted paranoia that one might hit the planet and cause massive destruction anyway). Norms once thought immutable were reconsidered as products of history and ambition and were therefore alterable. New methods could improve on or replace the old ways.

Science alone could be trusted for truth, now conceived as correspondent to verifiable facts. Empiricism is the natural philosophical presupposition of modern science. The focus on empiricism, and therefore experimentation, led many to fear that the Church and the Faith were soon to be revealed as mere relics of an ignorant and barbaric past. (As a side note: I highly recommend

How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas E Woods Jr.) In such a climate it is natural that theologians would seek ways to contemporize the Faith, to make it seem more modern and thus more acceptable to the emerging modern mindset.

Theologically, the focus shifted, at first ever so slightly and later much more profoundly. Spiritual things were seen as opposed to the material, the real, and the scientific. Mystical experiences, by their very nature often contrary to or beyond the categories of rational thought, were placed on the opposite side of a great divide from reason and logic. The balance seemed perfect: on the one hand, science, objectivity, reason; on the other hand, faith, subjectivity, mystical experience.

Practically speaking, this bifurcation separating the spiritual from the material allowed science to ascend to a place of religious-like dominance in culture. ("Better living through science" was but one of the familiar mottoes of the twentieth century.) The charge of unreasonableness in showing something to be contrary to observable fact became the habeas corpus to convict many older arguments and opinions. Occam's Razor took on nearly divine axiomatic superiority. "The facts speak for themselves." Applying the scientific method (to wit., analytical experimentation, observation and narrowly drawn conclusions) seemed the path to open the doors to a greater understanding of everything. It could be applied to history, sociology, politics and economics.

While the benefits of scientific progress for human society, viewed from a purely materialistic standpoint, were undeniable, for the spiritual life, the evolution of the new mindset has proven to be devastating. In seeking to contemporize religious dialogue and practice, theologians found their path truncated by the wall of separation dividing faith from reason. Religious discourse itself turned inward with a tacit acceptance that, since the very content of the dialogue was itself subjective, differing interpretations and explanations were to be expected.

To claim an objective truth for a religious belief or practice became seen as a retreat into a fantasy world of Dark Ages superstition and ignorance. Miracles were explainable; they were either natural events given a religious significance or myths not requiring reasonable assent at all. The parting of the Red Sea was an ebb tide; the light of Mount Tabor was the glint of sunlight on snow; the Resurrection was a metaphor indicating the ongoing significance of Jesus’ ethical teachings, etc.

This has been what passes for contemporary theology since at least the late 1800’s although, as noted earlier, the roots of this trend go back much further. Prevented from embracing the totality of its world of discourse, theology becomes either reductionistic or fundamentalist, in both cases accepting the diminished existence granted it by the modern and post-modern world.

Given such progressive developments, especially in the last century, we find ourselves today in a cultural climate that relegates religious discourse to the realm of the pseudo-intellectual. Secular atheism attempts to muzzle any religious discourse as ignorant, intolerant and unwelcome in the arena of public debate. The problem is compounded by the unconscious unwillingness of many theologians to challenge the basic assumptions that relegate faith to the private realm, or at best in the public realm as a mere tool for political or sociological ideologies.

It is widely decried that catechesis has been largely ignored or deformed by the ill-conceived 'trendy' interpretations of the last generation or so. "Faith seeking understanding" has been transformed into a "dress it up for modern consumption" approach.

Needless to say, the attempt to conduct catechesis in more contemporary ways has not produced laudable results. We now have generations of people who aren't sure what they believe or why, and whom are embarrassed that someone might point the finger and expose them as "one of those people" who ignorantly hold to superstition and/or attempt to enslave others to their own rules.

Catechesis, when practiced at all, is too often a platform to promote a political agenda, sociological innovation, or New Age-type self-focused psychological analysis. There is an almost visceral rejection of any attempt to catechize utilizing the fullness of discourse. Instead, while focusing on the subjective the catechumen is reminded to maintain a certain detached objectivity.

The fear of actually being discovered really to believe in something can immobilize. I actually once saw a man make the sign of the cross with all the pomp and circumstance of flicking away an after dinner crumb. ("I didn't want to draw attention to myself... it might offend!") It isn't that one isn't permitted to believe in something, but rather that one must not cross the line to claim it possesses an objective truth that might oppose or offend someone else.

This was the reason for the vitriol against

Dominus Iesus. The Catholic Church actually dared to proclaim that it still believed in all that 'old nonsense!'

(

How appallingly uncouth!)

What is needed is the courage to engage in religious discourse in all its fullness, the setting of appropriate priorities in life, and the challenge to accept open public commitment to the Truths of the Faith that alone can inspire, challenge, comfort and give real meaning to the totality of human existence.

This need has been recognized in the Church from the beginning. In one of his sermons on John's Gospel, St John Chrysostom wryly comments on the enthusiasm of the people for what today we might call 'secular' entertainment.

"They that are spectators of the heathen games, when they have learned that a distinguished athlete and winner of crowns is come from any quarter, run all together to view his wrestling, and all his skill and strength; and you may see the whole theater of many ten thousands, all there straining their eyes both of body and mind, that nothing of what is done may escape them. So again these same persons, if any admirable musician come amongst them, leave all that they had in hand, which often is necessary and pressing business, and mount the steps, and sit listening very attentively to the words and the accompaniments, and criticizing the agreement of the two. This is what the many do. Again; those who are skilled in rhetoric do just the same with respect to the sophists, for they too have their theaters, and their audience, and clappings of hands, and noise, and closest criticism of what is said." (First Homily on John )He goes on to gently remind his listeners that if they can be so enthusiastic for these things they should attend all the more to that which treats of God and things eternal.

The Golden-tongued knew the dangers of temptation of distraction. In our situation, that danger is even greater. Not only are the sources of distraction more numerous, but religious discourse has been allowed a smaller sphere in contemporary society than in ages past.

Yet, in another sense, little has changed since the days of John Chrysostom. Society still urges that we should spend our time (and treasure) on the latest fad or fashion (or electronic device). Modern culture pressures to suppress religious expression that might lead to actual reflection on whether such trendy pursuits have any lasting value. To perpetuate the focus on self and the pursuit of material pleasure society encourages the separation of Church from society, and faith from the Church. Distraction remains as tempting today as in the fifth century.

Thus, catechesis is conceived to be difficult and tedious. Better to be amused by any drug or distraction that comes along than to contemplate a reality that might have existential consequences for me and how I live my life. This is the allure of the New Age movement and the many do-it-yourself spirituality groups. Instead of experiencing the life of Faith in the Church, a life exploding with Divine Light and immortality, a sense of fantasy and ego seeks to find satisfaction in that which can never satisfy.

Catechesis requires dialogue with the living God. Society finds such conversation obscene. Neil Postman's book

Amusing Ourselves to Death provides provocative reflection on the dangers of distraction. While his focus is on particular media, the larger assertion and danger is easily extrapolated. I first read the book twenty years ago and have found it even more relevant today.

If you visit a Catholic bookstore, like

Pauline Books and Media (one of the best, in my opinion), and browse the "Adult Instruction" aisle you can find dozens of books on the Faith. Everything from the latest

Trivia of Church History for Dummies to the

Catechism of the Catholic Church. (There's even the wonderful reader's digest edition, the

Compendium!) The central Truths of the Faith can be examined and studied at the level of the mildly curious as well as from the perspective of the intense inquirer. The Compendium or the Catechism itself is the place to start. The ‘popular’ volumes are unfortunately too often infected with the modernist reductionism.

But ultimately, it is the courage and commitment to truly live the Faith that is important. How wonderful it would be if when we visit the Church instead of keeping an eye on the clock we kept our eyes on the great Mystery unfolding before us! How beautiful to realize God's love for us and to actually respond with love from the depths of our heart. How blessed to stand in the silence of His Divine Presence and let ourselves experience that compassion that not only created us but also continually seeks to draw us closer to Him. How precious to realize how close God is and the love with which he surrounds us.

That’s what the Christian Faith and the Catholic Church is all about, Charlie Brown!

If we allow ourselves to experience that love, catechesis will not be a problem. The Liturgy will reveal a melody of peace few could otherwise imagine. Instead of crumb-flicking signs of the Cross, we'll be offering that prayer with the confidence and open joy of the young man who wants the whole world to know he's in love and how wonderful his girlfriend really is. We'll find in the Scriptures, the prayers and teachings of the Church not just some dry study of what and why but a vibrant romance of God's desire for our love. We will discover that being a member of His Church is actually sharing in the life of the Trinity.

We will see that the Life Jesus shares with us is unique, intimate and an incomparable treasure.

In short, we'll find true joy and abundant life.

Or we could go just on amusing ourselves to death.