Summer Reading: How the Eight Hundred Men of Otranto Saved RomeFor the rest of this beautiful article, click here.

They were martyred five centuries ago in the easternmost region of Italy, the spot most exposed to attack from the Muslims. The objective of the caliph Mohammed II was to conquer Rome, after having already taken Constantinople. But he was stopped by Christians who were ready to defend the faith with their blood

by Sandro Magister

ROMA, August 14, 2007 – The Roman Martyrology, the liturgical calendar of saints and blesseds updated according to the decrees of Vatican Council II and promulgated by John Paul II, shows that today the Church remembers and venerates...

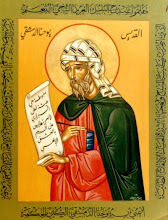

“... the approximately eight hundred martyrs of Otranto, in Puglia, pressured to renounce the faith after the crushing assault of the Ottoman soldiers. They were exhorted by blessed Antonio Primaldo, an elderly tailor, to persevere in Christ, and thus through decapitation they obtained the crown of martyrdom.”

The martyrdom of these eight hundred men took place in 1480, on August 14, the day of their liturgical commemoration.

It was because of them that five centuries later, in 1980, John Paul II visited Otranto, the Italian city in which they were martyred.

And this year, on July 6, Benedict XVI definitively authenticated their martyrdom, with a decree promulgated by the congregation for the causes of the saints.

But who were the eight hundred men of Otranto? And why were they killed? Their story is of extraordinary relevance – just like the conflict between Islam and Christianity, in the midst of which they sacrificed their lives.

This is presented in the account that follows – it appeared last July 14 in “il Foglio” – written by Alfredo Mantovano, a Catholic jurist, senator, and a son of the same land that produced those martyrs, born in southern Puglia, the region of Otranto.

“Ready to die a thousand times for Him...”

by Alfredo Mantovano

On July 6, 2007, Benedict XVI received a visit from the prefect of the congregation for the causes of saints, cardinal José Saraiva Martins, and authorized the publication of the decree of authentication for the martyrdom of blessed Antonio Primaldo and his lay companions, “killed out of hatred for the faith” in Otranto on August 14, 1480.

Antonio Primaldo’s is the only name that has come down to us. His companions in martyrdom were eight hundred unknown fishermen, craftsmen, shepherds, and farmers from a small town, whose blood, five centuries ago, was shed solely because they were Christian.

Eight hundred men, who five centuries ago suffered the treatment reserved in 2004 for the American antenna repairman Nick Berg, captured by Islamic terrorists in Iraq and killed to the cry of “Allah is great!” His executioner, after cutting his jugular, drew the blade around his neck until his head was detached, and then held this up as a trophy. Exactly as the Ottoman executioner did in 1480 to each of the eight hundred men from Otranto.

* * *

There is a prologue to this mass execution. In the early morning hours of July 29, 1480, from the walls of Otranto there could be seen on the horizon an approaching fleet composed of 90 galleys, 15 galleasses, and 48 galliots, with 18,000 soldiers on board. The armada was led by the pasha Ahmed, under the orders of Mohammed II, called Fatih, the Conqueror, the sultan who in 1451, at just 21 years of age, had become head of the Ottoman tribe, which had replaced the mosaic of Islamic emirates a century and a half earlier.

In 1453, at the head of an army of 260,000 Turks, Mohammed II had conquered Byzantium, the “second Rome,” and from that moment he developed the plan of wiping out the “first Rome,” Rome true and proper, and of turning Saint Peter’s basilica into a stall for his horses.

In June of 1480, he judged the time was right to go into action: he lifted the siege from Rhodes, which was defended courageously by its knights, and directed his fleet toward the Adriatic Sea. His intention was to land at Brindisi, which had an excellent, spacious harbor: from Brindisi, he planned to move northward up Italy until he reached the see of the papacy. But a strong contrary wind forced the ships to touch ground fifty miles to the south, and to disembark in a place called Roca, a few kilometers from Otranto.

* * *

Otranto was – and is – the easternmost city in Italy. It has a rich history: the immediate vicinity was probably inhabited in the Paleolithic period, and certainly from the Neolithic age. It was then populated by the Messapi, a race prior to the Greeks that was conquered by them, migrated to Magna Graecia, and fell into the hands of the Romans, becoming a Roman town.

The importance of its harbor had given it the role of a bridge between East and West, a role consolidated on the cultural and political level by the presence of an important monastery of Basilian monks, the monastery of San Nicola in Casole, of which a couple of columns remain on the road that leads to Leuca.

In 1095, in its splendid cathedral church built between 1080 and 1088, the blessing was imparted to the twelve thousand crusaders who, under the command of prince Boemondo I d’Altavilla, were leaving to liberate and protect the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. And on his return from the Holy Land, it was in Otranto that saint Francis of Assisi landed in 1219, and was received with great honor.

Tuesday, August 14, 2007

The Martyrs of Otranto

Please forgive, but Sandro's latest article has personal meaning for me.

Labels:

calendar,

Islam,

Otranto,

Pope,

Roman Martyrology

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment