Reorienting the Latin Rite Mass

2007-09-22

Father Lang Comments on

LONDON, SEPT. 21, 2007 (Zenit.org).- The statement asserting that the priest celebrating the older form of the Latin Rite Mass has "his back to the people" misses the point, says Father Uwe Michael Lang.

The posture "ad orientem," or "facing east," is about having a common direction of liturgical prayer, he adds.

Father Lang of the London Oratory, and recently appointed to work for the Pontifical Commission for the Cultural Heritage of the Church, is the author of "Turning Toward the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer." The book was first published in German by Johannes Verlag and then in English by Ignatius Press. The book has also appeared in Italian, French, Hungarian and Spanish.

In this interview with ZENIT, Father Lang speaks about the "ad orientem" posture and the possibilities for a rediscovery of the ancient liturgical practice.

Q: How did the practice of celebrating the liturgy "ad orientem," or "facing east," develop in the early Church? What is its theological significance?

Father Lang: In most major religions, the position taken in prayer and the layout of holy places is determined by a "sacred direction." The sacred direction in Judaism is toward Jerusalem or, more precisely, toward the presence of the transcendent God -- "shekinah" -- in the Holy of Holies of the Temple, as seen in Daniel 6:10.

Even after the destruction of the Temple, the custom of turning toward Jerusalem was kept in the liturgy of the synagogue. This is how the Jews have expressed their eschatological hope for the coming of the Messiah, the rebuilding of the Temple, and the gathering of God's people from the diaspora.

The early Christians no longer turned toward the earthly Jerusalem, but toward the new, heavenly Jerusalem. It was their firm belief that when the Risen Christ would come again in glory, he would gather his faithful to make up this heavenly city.

They saw in the rising sun a symbol of the Resurrection and of the Second Coming, and it was a matter of course for them to pray facing this direction. There is strong evidence of eastward prayer in most parts of the Christian world from the second century onward.

In the New Testament, the special significance of the eastward direction for worship is not explicit.

Even so, tradition has found many biblical references for this symbolism, for instance: the "sun of righteousness" in Malachi 4:2; the "day dawning from on high" in Luke 1:78; the angel ascending from the rising of the sun with the seal of the living God in Revelation 7:2; and the imagery of light in St John's Gospel.

In Matthew 24:27-30, the sign of the coming of the Son of Man with power and great glory, which appears as the lightning from the east and shines as far as the west, is the cross.

There is a close connection between eastward prayer and the cross; this is evident by the fourth century, if not earlier. In synagogues of this period, the corner with the receptacle for the Torah scrolls indicated the direction of prayer -- "qibla" -- toward Jerusalem.

Among Christians, it became a general custom to mark the direction of prayer with a cross on the east wall in the apses of basilicas as well as in private rooms, for example, of monks and solitaries.

Toward the end of the first millennium, we find theologians of different traditions noting that prayer facing east is one of the practices distinguishing Christianity from the other religions of the Near East: Jews pray toward Jerusalem, Muslims pray toward Mecca, but Christians pray toward the east.

Q: Do any of the other rites of the Catholic Church employ the "ad orientem" liturgical posture?

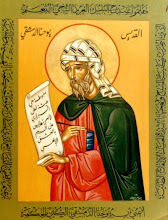

Father Lang: "Facing east" in liturgical prayer is part of the Byzantine, Syriac, Armenian, Coptic and Ethiopian traditions. It is still the custom in most of the Eastern rites, at least during the Eucharistic prayer.

A few Eastern Catholic Churches -- for example, the Maronite and the Syro-Malabar -- have lately adopted "Mass facing the people," but this is owing to modern Western influence and not in keeping with their authentic traditions.

For this reason, the Vatican Congregation for Eastern Churches declared in 1996 that the ancient tradition of praying toward the east has a profound liturgical and spiritual value and must be preserved in the Eastern rites.

Q: We often hear that "facing east" means the priest is celebrating "with his back to the people." What is really going on when the priest celebrates Mass "ad orientem"?

Father Lang: That catchphrase often heard nowadays, that the priest "is turning his back on the people," misses the crucial point that the Mass is a common act of worship in which priest and people together -- representing the pilgrim Church -- reach out for the transcendent God.

What is at issue here is not the celebration "toward the people" or "away from the people," but rather the common direction of liturgical prayer. This is maintained whether or not the altar is literally facing east; in the West, many churches built since the 16th century are no longer "oriented" in the strict sense.

By facing the same direction as the faithful when he stands at the altar, the priest leads the people of God on their journey of faith. This movement toward the Lord has found sublime expression in the sanctuaries of many churches of the first millennium, where representations of the cross or of the glorified Christ illustrate the goal of the assembly's earthly pilgrimage.

Looking out for the Lord keeps the eschatological character of the Eucharist alive and reminds us that the celebration of the sacrament is a participation in the heavenly liturgy and a pledge of future glory in the presence of the living God.

This gives the Eucharist its greatness, saving the individual community from closing in upon itself and opening it toward the assembly of the angels and saints in the heavenly city.

Q: In what ways does "facing east" during the liturgy foster a dialogue with the Lord?

Father Lang: The paramount principle of Christian worship is the dialogue between the people of God as a whole, including the celebrant, and God, to whom their prayer is addressed.

This is why the French liturgist Marcel Metzger argues that the phrases "facing the people" and "back to the people" exclude the one to whom all prayer is directed, namely God.

The priest does not celebrate the Eucharist "facing the people," whatever direction he faces; rather, the whole congregation celebrates facing God, through Jesus Christ and in the Holy Spirit.

Q: In the foreword to your book, then Cardinal Ratzinger notes that none of the documents of the Second Vatican Council asked for the altar to be turned toward the people. How did this change come about? What was the basis for such a major reorientation of the liturgy?

Father Lang: Two main arguments in favor of the celebrant's position facing the people are usually presented.

First, it is often said that this was the practice of the early Church, which should be the norm for our age; however, a close study of the sources shows that this claim does not hold.

Second, it is maintained that the "active participation" of the faithful, a principle that was introduced by Pope Pius X and is central to "Sacrosanctum Concilium," demanded celebration toward the people.

Recent critical reflection on the concept of "active participation" has revealed the need for a theological reappraisal of this important principle.

In his book "The Spirit of the Liturgy," then Cardinal Ratzinger draws a useful distinction between participation in the Liturgy of the Word, which includes external actions, and participation in the Liturgy of the Eucharist, where external actions are quite secondary, since the interior participation of prayer is the heart of the matter.

The Holy Father's recent postsynodal apostolic exhortation "Sacramentum Caritatis" has an important discussion of this topic in Paragraph 52.

Q: Is a priest forbidden from "facing east" in the new order of the Mass promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1970? Is there any juridical obstacle prohibiting wider use of this ancient practice?

Father Lang: A combination of priest and people facing each other during the Liturgy of the Word and turning jointly toward the altar during the Liturgy of the Eucharist, especially for the Canon, is a legitimate option in the Missal of Pope Paul VI.

The revised General Instruction of the Roman Missal, which was first published for study purposes in 2000, addresses the altar question in Paragraph 299; it seems to declare the position of the celebrant "ad orientem" undesirable or even prohibited.

However, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Sacraments rejected this interpretation in a response to a question submitted by Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, archbishop of Vienna. Obviously, the relevant paragraph of the General Instruction must be read in light of this response, which was dated Sept. 25, 2000.

Q: Will Pope Benedict's recent apostolic letter liberalizing the use of the Missal of John XXIII, "Summorum Pontificum," foster a deeper appreciation for "turning toward the Lord" during the Mass?

Father Lang: I think many reservations or even fears about Mass "ad orientem" come from lack of familiarity with it, and the spread of the "extraordinary use" of the Roman rite will help many people to discover and appreciate this form of celebration.

ZE07092103 - 2007-09-21

Monday, September 24, 2007

Facing the Lord? or Giving People the Back?

Fr Lang has a clear knowledge of history and liturgical theology. What too many 'progressives' in the Roman Church forget is that up until the 'reforms' of the Second Vatican Council, all Catholic and Orthodox priests faced the same direction during the Liturgy, liturgical east. So much for "giving 'em the back!"

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment