10. Do not cast off brotherly love lightly, for there remains no other way of salvation for human beings. Observe yourself with care, and see if the evil which separates you from your brother has its cause, not in him, but in you, and make haste to be reconciled with him, let you transgress the commandment of love. Do not despise the commandment of love, because through it you will become a son of God, whereas, when you transgress it, you will become a son of Gehenna.

11. Do not seek to please yourself, and you will not hate your brother; do not indulge in self-love, and you will love God. If you have chosen to live with spiritual brothers, renounce your will from the moment you pass through the doors of the monastery; for in no other way will you be able to live in peace, either with God or with those with whom you dwell.

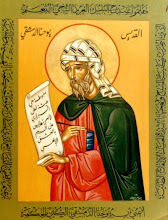

St Maximos the Confessor, The Evergetinos: A Complete Text, Volume I, p. 351

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Wisdom from the Church Fathers

As there is not a single superfluous word in the Church's Divine Services, it is especially necessary at the time of the singing of the Litany of Fervent Supplication (the "Ecumenic Petitions") to pray to God most fervently, from the very depths of a most contrite heart, as we are reminded at the very beginning of the litany by the words: "Let us all say with our whole souls and with our whole mind, let us all say...."

St. John of Kronstadt

We would do well to have St John's phronema when preparing liturgical texts or celebrating the Divine Services, especially when tempted to view "economy" in terms of brevity, 'simplification', and removal of the "unnecessary". If we are truthful in claiming we desire to stand on the right hand on the Day of Resurrection, spending a few extra minutes in Church should not be a burden. Father Paul Tarazi recalled that once when he was asked why we chant "Lord, have mercy" forty times, that he replied, "Forty? Why not Four hundred times?!" When I find myself bored in church, I should ask myself why does it seem so to me, not why is it taking so long.

St. John of Kronstadt

We would do well to have St John's phronema when preparing liturgical texts or celebrating the Divine Services, especially when tempted to view "economy" in terms of brevity, 'simplification', and removal of the "unnecessary". If we are truthful in claiming we desire to stand on the right hand on the Day of Resurrection, spending a few extra minutes in Church should not be a burden. Father Paul Tarazi recalled that once when he was asked why we chant "Lord, have mercy" forty times, that he replied, "Forty? Why not Four hundred times?!" When I find myself bored in church, I should ask myself why does it seem so to me, not why is it taking so long.

Labels:

asceticism,

Church Fathers,

Divine Liturgy,

Great Lent,

wisdom

Friday, February 26, 2010

Wisdom from the Church Fathers

Do not be surprised if you fall back into your old ways every day. Do not be disheartened, but resolve to do something positive about it; and, without question, the angel who stands guard over you will honour your perseverance.

St John Klimakos, The Ladder of Divine Ascent

St John Klimakos, The Ladder of Divine Ascent

Labels:

asceticism,

Church Fathers,

Great Lent,

spirituality

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Depressed? Get God, Get Happy!

The Washington Times reports that two respected studies have revealed that belief in God helps people deal with problems and sickness with less depression.

Who'd have thunk it?

Read the entire article here.

The researchers compared the levels of melancholy or hopelessness in 136 adults diagnosed with major depression or bipolar depression with their sense of "religious well-being." They found participants who scored in the top third of a scale charting a sense of religious well-being were 75 percent more likely to get better with medical treatment for clinical depression.

"In our study, the positive response to medication had little to do with the feeling of hope that typically accompanies spiritual belief," said study director Patricia Murphy, a chaplain at Rush and an assistant professor of religion, health and human values.

"It was tied specifically to the belief that a Supreme Being cared," she said.

Who'd have thunk it?

Read the entire article here.

Wisdom from the Church Fathers

Fire makes iron impossible to touch, and likewise frequent prayer renders the intellect more forceful in its warfare against the enemy. That is why the demons strive with all their strength to make us slothful in attentiveness to prayer, for they know that prayer is the intellect's invincible weapon against them.

St John of Karpathos

St John of Karpathos

Labels:

asceticism,

Church Fathers,

Great Lent,

wisdom

Monday, February 22, 2010

Wisdom from the Church Fathers

Not every person is able to achieve the highest state of transcendent soul; but it is certainly possible for everyone to find reconciliation with God, and it is this that will save them.

St John Klimakos

St John Klimakos

Labels:

asceticism,

Church Fathers,

Great Lent,

John of the Ladder,

wisdom

Friday, February 19, 2010

Wisdom from the Church Fathers

Loving one's enemies does not mean loving wickedness, ungodliness, adultery, or theft. Rather, it means loving the thief, the ungodly, and the adulterer.

Clement of Alexandria 195 A.D.

Clement of Alexandria 195 A.D.

Labels:

asceticism,

Church Fathers,

Great Lent,

wisdom

Thursday, February 18, 2010

Wisdom from the Church Fathers

Just as it is only after labor that a pregnant woman gives birth to the fruit that gives joy, so it is with the soul: only after labours is knowledge of the mysteries of God given birth in it.

St Isaac of Syria

St Isaac of Syria

Labels:

asceticism,

Church Fathers,

Great Lent,

wisdom

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Wisdom from the Church Fathers

21. Some people living carelessly in the world have asked me: "We have wives and are beset with social cares, and how can we lead the solitary life?" I replied to them: "Do all the good you can; do not speak evil of anyone; do not steal from anyone; do not lie to anyone; do not be arrogant towards anyone do not hate anyone; do not be absent from the divine services; be compassionate to the needy; do not offend anyone, do not wreck another man's domestic happiness, and be content with what your own wives can give you. If you behave in this way, you will not be far from the Kingdom of Heaven.The Ladder of Divine Ascent, St John Climacus, Holy Transfiguration Monatery Press, Boston, MA, 1991, page 9.

Labels:

asceticism,

Church Fathers,

Great Lent,

John of the Ladder,

wisdom

Monday, February 15, 2010

Serious (sic) Advice for Great Lent

Have a Miserable Lent!

What are you doing surfing the Web?! You should be PRAYING!

I don't hear your stomach rumbling! I'll bet you ATE TOO MUCH today!

You probably ATE TOO MUCH because your TEETH DON'T HURT ENOUGH -- because you haven't been GNASHING them enough!

You're not wearing STREET CLOTHES are you? Where's your SACKCLOTH? Say, that sackcloth looks UNTORN!

WHERE'S YOUR HAIRSHIRT?

WHAT WERE YOU THINKING?!?!?!

What are you doing surfing the Web?! You should be PRAYING!

I don't hear your stomach rumbling! I'll bet you ATE TOO MUCH today!

You probably ATE TOO MUCH because your TEETH DON'T HURT ENOUGH -- because you haven't been GNASHING them enough!

You're not wearing STREET CLOTHES are you? Where's your SACKCLOTH? Say, that sackcloth looks UNTORN!

WHERE'S YOUR HAIRSHIRT?

WHAT WERE YOU THINKING?!?!?!

"Is outrage!" exclaimed Father Vasiliy

Advices on spiritual experiences with temptations and sorrows

By Saint Isaac the Syrian.

Just as the eyebrows approach each other, so are the temptations close to men. It was the economy of God to be so, with wisdom that we may receive benefit: namely, through knocking persistently, because of the sorrows, on the door of God's mercy and to enter into your mind, due to the fear of grievous events, the seed of memory of God, so that you may approach Him with supplications and your heart be sanctified through the continuous remembrance of Him. And while you ask Him, He will listen.

Just as the eyebrows approach each other, so are the temptations close to men. It was the economy of God to be so, with wisdom that we may receive benefit: namely, through knocking persistently, because of the sorrows, on the door of God's mercy and to enter into your mind, due to the fear of grievous events, the seed of memory of God, so that you may approach Him with supplications and your heart be sanctified through the continuous remembrance of Him. And while you ask Him, He will listen.

- The person walking the road of God must thank Him for all the sorrows that he faces, and to accuse and dishonor his negligent self, and know that the Lord who loves and looks after him, would not have allowed the grievous things to happen to wake his mind up, if he had somehow not been negligent. God may have allowed some sorrow because man has become proud and consequently he should understand and let him not become disturbed but find the cause within himself, so that the affliction may not double up, namely suffer and not wish to be treated. "In God who is the source of justice there is no injustice". May we not think otherwise.

- Do not avoid the sorrows, because being helped by them you learn the truth and love of God well. And do not fear the temptations (negative experiences) for through them you discover treasures. Pray that you may not enter into spiritual temptations, while for the bodily ones, prepare to face them with all your strength, for without them you cannot approach God. Through them comes the divine rest. Whoever avoids the bodily temptations avoids virtue.

Labels:

Church Fathers,

Great Lent,

St Isaac the Syrian,

wisdom

Friday, February 12, 2010

Advice on the Great Fast From the Church Fathers

It is better to eat meat and drink wine and not to eat the flesh of one's brethren through slander.

Abba Hyperechios

It is necessary most of all for one who is fasting to curb anger, to accustom himself to meekness and condescension, to have a contrite heart, to repulse impure thoughts and desires, to examine his conscience, to put his mind to the test and to verify what good has been done by us in this or any other week, and which deficiency we have corrected in ourselves in the present week. This is true fasting.

St. John Chrysostom

Abba Hyperechios

It is necessary most of all for one who is fasting to curb anger, to accustom himself to meekness and condescension, to have a contrite heart, to repulse impure thoughts and desires, to examine his conscience, to put his mind to the test and to verify what good has been done by us in this or any other week, and which deficiency we have corrected in ourselves in the present week. This is true fasting.

St. John Chrysostom

Labels:

Church Fathers,

fasting,

Great Lent,

wisdom

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Ladder of Divine Ascent - Lenten Reading Schedule

Thanks to Archpriest Michael Hayduk and Father Deacon Paul J. Leonarczyk, for the schema to read through St John of Sinai's Ladder of Divine Ascent during the Great Fast. The Ladder (from which St John received the 'nickname" Klimakos - "ladder" in Greek) was written in response to another Abbot's advice on promoting health spirituality in his monastery. St John's reply proved such a thorough and clear exposition that it has become de rigueur Lenten reading in Eastern Christians monasteries all over the world. As St John's writings are also easily accessible to the average reader, it has also become a favorite among the Byzantine Catholic and Orthodox laity as well. It is easily found in several English editions, the two most widely available being John Climacus: The Ladder of Divine Ascent (The Classics of Western Spirituality) and as The Ladder of Divine Ascent, published by Holy Transfiguration Monastery. Both are highly readable, the Holy Transfiguration Monastery edition perhaps presenting a more erudite and nuanced translation.

Below is the arrangement for those who keep the Horologion. For those unacquainted with "the Hours" Third=9:00 am; Sixth=Noon; ninth=3:00 pm (approximately). One could also easily consider a time-table dividing as "on rising", "after work" and "near bedtime"; or even combining selections of the individual daily readings as one chooses. In any event, the Ladder is, after the Scriptures and Divine Services of the Season, the par excellence choice for Lenten reading.

Below is the arrangement for those who keep the Horologion. For those unacquainted with "the Hours" Third=9:00 am; Sixth=Noon; ninth=3:00 pm (approximately). One could also easily consider a time-table dividing as "on rising", "after work" and "near bedtime"; or even combining selections of the individual daily readings as one chooses. In any event, the Ladder is, after the Scriptures and Divine Services of the Season, the par excellence choice for Lenten reading.

Labels:

asceticism,

Books,

Great Lent,

prayer,

Readings,

spirituality

Friday, February 05, 2010

A Day at School

Yesterday, I had the privilege of spending the day at a local parochial high school speaking with students taking religion/theology classes. The original idea was that as an Eastern priest I would supplement the professor's lectures/discussions on the topic at hand with the Byzantine perspective. This was interesting in itself as I found them be intelligent, thoughtful and interested in hearing different opinions and views. They were very polite and commendable youngsters (yes, I'm old enough to join the ranks of Ed Sullivan in calling them "youngsters"). Thus, by the end of the second class, the professor and I decided that it might be interesting if I simply presented the option to either speak on their recent subject of study or offer a period of free-wheeling questions and answers.

It should surprise no one that given the option, the overwhelming choice was the Q&A format.

Now to set the scene so that you don't misinterpret the atmosphere of the classroom, I wasn't there in "civvies" (although, an argument could be made that in reality I was in civvies), I was in my customary Anteri, sporting a pectoral Russian-style crucifix, and a skouphos. In a generation of young people conditioned to see 'celebrities' in all manner of dress - exotic dress, partial dress, and even eye-averting undress - my simple garb still managed to draw attention and provoke a few questions.

"What's that on you head?"

"A hat. Next question...." - Actually, I gave a more serious reply after the joking one.

It should surprise no one that given the option, the overwhelming choice was the Q&A format.

Now to set the scene so that you don't misinterpret the atmosphere of the classroom, I wasn't there in "civvies" (although, an argument could be made that in reality I was in civvies), I was in my customary Anteri, sporting a pectoral Russian-style crucifix, and a skouphos. In a generation of young people conditioned to see 'celebrities' in all manner of dress - exotic dress, partial dress, and even eye-averting undress - my simple garb still managed to draw attention and provoke a few questions.

"What's that on you head?"

"A hat. Next question...." - Actually, I gave a more serious reply after the joking one.

Wednesday, February 03, 2010

Another Option for Lenten Prayer Regime

The Icon of Our Lady the Softener of Evil Hearts is both a spiritually stunning and miraculous Icon from Russia, the Akathist to Our Lady the Softener of Evil Hearts is also a beautiful meditation that deserves consideration for those seeking a wholesome addition to their Lenten discipline. The Akathist is provide via H/T from Eirenikon.

Below is the text of the Akathist as taken from Eirenikon's Blog - which should be high on your list of bookmarks and favorites!

Below is the text of the Akathist as taken from Eirenikon's Blog - which should be high on your list of bookmarks and favorites!

The Apolytikion in Tone 5

Soften our evil hearts, O Theotokos, * and quench the attacks of those who hate us * and loose all straitness of our soul. * For looking on thy holy icon * we are filled with compunction by thy suffering and loving-kindness for us * and we kiss thy wounds; * we are filled with horror for the darts with which we wound thee. * Let us not, O Mother of Compassion, * according to the cruelty of our hearts, perish from the cruelty of heart of those near us, ** For thou art in truth the Softener of Evil Hearts.

Kontakion I

We cry out with heartfelt emotion to the chosen Virgin Mary, far nobler than all the daughters of the earth, Mother of the Son of God, Who gave salvation to the world: Look at our life which is filled with every sorrow and remember the sorrow and pain which thou didst suffer as one born on earth with us, and do with us according to thy merciful heart, that we may cry unto thee: Rejoice, much-sorrowing Mother of God, turn our sorrows into joy and soften the hearts of evil men!

Oikos I

An angel announced the birth of the Saviour of the world to the shepherds in Bethlehem and with the multitude of the heavenly hosts praised God, singing: “Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace, good will among men!” But thou, O Mother of God, having nowhere to lay thy head, since there was no room in the inn, gave birth to thy first-born Son in a cave and, wrapping Him in swaddling clothes, laid Him in a manger. Knowing the pain in thy heart, we cry out to thee:

Rejoice, for thou wast warmed by the breath of thine own beloved Son!

Rejoice, for thou didst wrap the eternal Child in swaddling clothes!

Rejoice, for thou didst nourish with thy milk the One who sustaineth the universe!

Rejoice, for thou didst turn a cave into a heaven!

Rejoice, for thou didst make thy throne upon the Cherubim!

Rejoice, for thou didst remain a virgin both in giving birth and after birth!

Rejoice, much-sorrowing Mother of God, turn our sorrows into joy and soften the hearts of evil men!

Labels:

akathist,

devotion,

Great Lent,

Prayers,

spirituality,

Theotokos

Tuesday, February 02, 2010

Reply to Question about Fasting and Abstinence

The below was written in response to a letter asking questions about Byzantine fasting practices. While I did not directly answer all of the questions put forth, I hope that my reply encompassed enough for prayerful consideration. At the end of my rejoinder I included (and reproduce here) Fr Athanasios Demos' How to Fast During Lent article - a most thorough and spiritually useful guide for all attempting to take the Holy Season seriously.

Dear N.;

May the All Holy Trinity bless you with peace, love and faith now and always!

Thank you for the note. Fasting in the Byzantine Tradition is a somewhat complex and diverse subject. First, a few basic notes. When one fasts, nothing passes the lips (water and medicines excluded) until Noon. Then one may have two meals that together do not equate with one regular non-fasting meal. It is true that different Churches have variations on the rules for abstinence. The main thing for the individual person would be to be consistent in whichever set of rules chosen for the particular fasting season.

The actual practice regarding abstinence is called Xerophagy – "dry eating". This implies that the foods consumed be natural with little fancy preparation. So, for example, spinach could be cooked, but with no additional condiments, etc..

Also the prohibition on meat includes most fish – a commonly misunderstood point. Only sea creatures that do not have scales, blood or a backbone may be eaten – i.e., creatures like shellfish or squid. Here we see the clear effect of location and culture in fasting practice as these creatures were very common and inexpensive in the Mediterranean world and considered peasants’ foods.

Labels:

answer to question,

athanasios demos,

fasting,

Great Lent,

spirituality

Monday, February 01, 2010

Practical Advice on Fasting

I shall speak first about control of the stomach, the opposite to gluttony, and about how to fast and what and how much to eat. I shall say nothing on my own account, but only what I have received from the Holy Fathers. They have not given us only a single rule for fasting or a single standard and measure for eating, because not everyone has the same strength; age, illness or delicacy of body create differences. But they have given us all a single goal: to avoid over-eating and the filling of our bellies... A clear rule for self-control handed down by the Fathers is this: stop eating while still hungry and do not continue until you are satisfied.

-St. John Cassian

-St. John Cassian

A Critique of the Melkite English Divine Liturgy Project's "Final Draft"

This critique references the edition of the Common Language Translation of the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom as promulgated 27 January 2009 by the Eparchy of Newton for Melkites in the USA

From the beginning, our little community has participated in the trial use of the several editions of the Common Language Translation project for English-speaking Melkites. With each new released edition, we have taken full advantage of the options permitted and tried them all out at least once. Ultimately, we have returned to the traditional 'options' and practices that have proven themselves efficacious for all Byzantine Rite Christians following the Typikon of the Great Church. That said, a review of the project's "Final Draft" is in order.

THE FINAL DRAFT AND PROCESS OF ESTABLISHING A COMMON ENGLISH TRANSLATION FOR ALL BYZANTINE RITE CHRISTIANS

The goal of a common text of the Divine Liturgy for English-speaking members of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church is a laudable one. A tragedy for the development of Byzantine Christianity in the Americas and other English-speaking regions has been the history of ad hoc translating, with both Catholic and Orthodox jurisdictions acting independently, and some jurisdictions producing various efforts of individuals having no coordination or support from the hierarchy. It is not uncommon to find that one jurisdiction may have two, five or more ‘approved’ (or commonly employed) translations each featuring twists of phrasing, anomalies and idiosyncrasies. This discordant reality makes a visit to another parish of ones own jurisdiction an adventure in attempting to avoid stumbling over linguistic variations not encountered in ones own parish. Compound this with the number of translations produced by ‘other’ jurisdictions and the frustration and confusion of the laity across the board becomes easily appreciated.

The fact that English is one of the few modern languages experiencing this frustrating, and spiritually stunting, situation is understandable given the historic context of the waves of distinct immigrations to the “New World”. The various small pockets of individual Eastern Christian communities were typically viewed by their “Old World” hierarchy as living in diasporas. Thus, they were encouraged to continue using the old language versions of the Divine Services and prayers rather than to produce English editions for the generations that would follow. Thus, while other linguistic nations moved to produce suitable translations in the new language, many of which have become the standard used by all Byzantine tradition Christians speaking said language, one may literally fill a bookcase with the numerous English editions of the Divine Liturgy produced by various Orthodox and Catholic jurisdictions over the years, each featuring their own merits and deficits, their own inspiring turns of phrase, their own clumsy or downright incomprehensible translations.

Given this historic context, the new Common English Language translation project by the Melkites is laudable in its intentions. One could take from the very fact of the project a hope that once finalized the resulting product might provide the springboard for the production of a common English translation for all Byzantine Rite Catholics. Indeed, one could dream of the day in which such efforts would lead to a definitive English edition that all Byzantine Christians, Orthodox and Catholic, could agree on for their jurisdictions’ regular worship.

Accepting the wholesomeness of the goal to produce a standard edition of the Divine Liturgy for English-speaking Melkites, it is in order to consider the results of the efforts made thus far. This is particularly important now as the currently released edition is proclaimed the “final draft”. Therefore a careful review of the draft’s accuracy of text, rubrics, and format deserves serious review. In addition, and more importantly, the quality of the English text that is being promulgated needs very careful consideration.

THE FINAL DRAFT – ITS GOALS, LIMITATIONS ON THE PROJECT AND RESULTANT TRANSLATION ISSUES

For the US edition of the Final Draft, the Eparch has provided an “Instruction” that serves as a general introduction as well as explanation for the selection of several particular translation choices. The Instruction notes that the English translation is the result of a process that began with the “the official Greek text”, followed by “the official Arabic translation as approved by the Melkite Holy Synod in 2005". The English translation is portrayed as the next step in the process of bringing to the vernacular the fruits of the Apostolic Tradition embodied in the original texts.

Emphasis immediately must be given to the fact that the translators were required to produce an English translation that conformed to the Arabic in all particulars rather than the “official Greek text”. The significance for this is understandable, but ultimately controversial. In terms of the particular customs and idiosyncrasies of the Melkite usage, it is natural that following the Arabic texts approved by the Holy Synod is a commendable choice. However, for the text of the Liturgy itself, such an approach is problematic; the English Final Draft is a translation of a translation. This is the very criticism of such English language Bible translations as the Douay, the Confraternity Edition, and the original translation of the Jerusalem Bible. While not condemnatory in and of itself, such an approach should always be guided by reference to the original text, and where peculiarities or questions arise weight be properly given to the original. (Note that this approach would actually strengthen the argument for reliance on the Septuagint as the basis for English translations of the Old Testament rather than relying on Hebrew, and in particular the Masoretic text.) There are nuances in every word and turn of phrase in any language that when employed can convey more accurately the originals meaning in translation; but if the translation is used as the authorized text for translation into a third language the resulting phrasing may be completely misleading.

The quintessential example of this is in the case of the Final Draft is the choice to use “now and always and forever and ever” versus the traditional English rendering “now and ever and to the ages of ages”. The stated justification for this choice in the Instruction is “that every major modern translation of these words in Scripture…employs the former, forever and ever.” One could be forgiven for viewing this choice as trivial. However, the original Greek Scriptures, the Divine Services and various commentaries of the Church Fathers use the term translated “ages” with specific import and meaning. In Greek the phrase “now and ever” or “now and always” already conveys the sense of “forever” before including the phrase “ages of ages”.

The term “age” in Greek has specific connotations indicating more than the simple measuring of time, and to render the phrase as “for ever and ever” is as potentially misleading as assuming that “era” carries no significant distinction than, say, “recent years”. (Please note that “forever” is specifically and consistently rendered “for ever” in the Revised Standard Version hinting at the distinction of “unto ages” versus “forever” in the original Greek.) “To the ages of ages” indicates not just an endless passage of time, but the taking into account of every age, era and circumstance. It clarifies the glory due to God as possessing a fullness that extends beyond all created realities. Thus, the selection of “for ever and ever” subtracts from translational accuracy and weakens the theological import of the original Greek.

Similarly, the substitution of “forgive me” for the expression “be propitious to me” is justified in the “Instruction” as being “clear and accessible in conveying the same meaning”. In fact, this simply is not so. The term propitious implies kindness, mercy and a favorable disposition. Thus, traditional (commonly chosen) English translations have utilized phrases such as “have mercy on me and forgive me” or “be propitious to me and forgive me”. The simplification (reduction) of the phrase to “forgive me” alone removes the dialogic framework of the prayer, actually omits the reference to God’s great mercy, and thereby ignores the very reason one can ask to be forgiven. This is at best a deficient paraphrase and at worst a gross lack of fidelity to the original.

Other examples of poor translation can be seen in the hymn to the Theotokos “It is truly right”. The translation’s text betrays an inferior understanding of the Incarnation by choosing “you gave birth to God the word in virginity” versus the more accurate translation “without corruption you gave birth to God the Word”. The word “corruption” is an exact translation of the Greek, which does not refer to sexual intercourse but rather the general corruption of human nature. It therefore conveys the truth that the Virgin conceived and gave birth to our Lord without the corruption of ancestral sin.

It must also be noted that the translation ends: “You are truly Theotokos, you do we exalt.” Given that in context the English word “magnify” is a direct translation of the Greek and, indeed, one may argue a cognate term, the justification for using “exalt” can only be that it happens to be the inferior term used by Baron De Vinck and Archbishop Raya (of blessed memory) in their original translations over a half century ago.

THE FINAL DRAFT AND INJUDICIOUS TRANSLATION DECISIONS

These examples demonstrate the principle difficulty with the translation. The translators were apparently restricted to conform their work to a translation (Arabic) of the original (Greek) instead of working directly from that original. To this was coupled the problem that the project freely borrows from pre-existing English-speaking Melkites translations. These prior works produced by translators for whom English was not their primary language, often employ awkward phraseology. These two facts combine to weaken the translation in many ways.

For example, a typical Ekphonesis (doxological conclusion to a prayer) in the Final Draft reads, “That being ever protected by Your power we may render glory to You, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, now and always and forever and ever.” The issue here is the absence of prepositions and articles for “Father, Son and Holy Spirit.” In Greek, “to the” is clearly implied by the repetition of the conjunction “and”. An exact word for word translation of the phrase from Greek would be “to (the) Father and (to the) Son and (to the) Holy Spirit…” The Greek nouns used in such a construction clearly indicate a comprehension that 'reads' “to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit”. The inflected form of the nouns carries the prepositional connection with it.

It begs the question to ask why the option to translate Trinitarian references using fuller, more majestic phrasing was passed over. One can only assume that to one for whom English is a second or third language the nuanced differences in English syntactical construction went unnoticed. However, the lack of the full prepositional phrases in the conjunction weakens the Trinitarian emphasis inherent in the original Greek. As translated in the Final Draft the Trinitarian reference could too easily be misinterpreted as modalistic rather than hypostatic.

Again, the problem originates in the directive to produce a text that mirrored the Arabic as exactly as possible. It seems that the majority of the editors, having English as a second or third language, misunderstood the impact of narrowing of the phrase would threaten to have on weakening the Trinitarian reference for the English worshipper and opted to approve a phrasing that mirrors the ‘letter’ of the source but diminishes theological nuance in the product. In the Final Draft’s phrasing of almost all Ekphoneses, the Persons of the Trinity grammatically become almost an afterthought. A more thorough acquaintance with English would have avoided this. A more careful adherence to the original Greek would have necessarily precluded it altogether.

The fault is in the directive to work from the Arabic instead of the Greek. A more rational approach would have been to translate from the Greek and compare the results with the Arabic. This would have undoubtedly produced a more accurate work in English while allowing for reasonable conformity with the Arabic.

RUBRICS, OPTIONS AND FORMATS

One distinctive problem with the released edition of the Final Draft is absence of rubrics. By definition, rubrics provide clear explanation of the movements and actions accompanying the text of the ritual. Unfortunately, the Final Draft provides vague descriptions of the teleturgical action that in no way promote basic conformity amongst the English-speaking clergy. The aim seems to have been to provide the laity with a basic understanding of what the clergy are doing during at any particular moment in the Liturgy. However, as with earlier drafts, the officially released volume is organized like a study text. The liturgical flow is repeatedly interrupted by ‘rubrics’ that diverge to note various options requiring the worshipper to anticipate which option a particular community follows and know how far to skip ahead to keep up with the given celebration. While earlier drafts at least occasionally noted the options and place more detailed information at the end of the volume, the Final Draft seeks to provide information about various optional practices in great detail at the exact point in the text of the liturgy wherein they occur. The result is an extremely unfriendly user’s edition. (A side note: As no discussion has yet been formalized concerning a ‘definitive’ translation of the Divine Liturgy of St Basil the Great, it is curious that several prayers from that Liturgy are included in the work under consideration.)

Amongst the various options allowed for the antiphons after the open litanies, the Final Draft does allow the Beatitudes along with the basic stichera from the Octoechos. This is extremely welcome as it allows the laity to experience more of the rich hymnody of the Church, with perhaps a goal of encouraging more participation in the offering of Great Vespers, Orthros or other Divine Services that sadly tend to be forgotten in many Melkite communities today. It must be noted, however, that for a project that intends to unite the English-speaking Melkites in using one text with specifically delineated options, it is somewhat ironic that at the end of the Beatitudes in each Tone the text includes two separate translations of its Troparion of the Resurrection. Obviously no consensus has been reached on a standard text for these commonly used troparia.

This also brings to the fore the question of the legitimacy of some of the options themselves. Here and there options are presented that obviously reflect the spirit of the Roman Church's post-Vatican II ‘people’s participation’. For example, the Ektene after the homily presents an option in which ‘readers’ chosen from the laity stand in the “middle aisle” facing each other and offer petitions from a large collection at the end of the volume. (The text is silent whether additional ‘made up’ petitions are allowed.) In short, a practice is being introduced that is a direct copy of the Roman Novus Ordo practice of "general intercessions" after the homily – a practice that is, to my knowledge, without precedent in the Byzantine Tradition.

The directions for the litanies after the homily also are troublesome from a theological perspective. The Litany of the Catechumens is directed to be done only “if there are Catechumens” present, and only one of the Prayers of the Faithful is to be included “(for brevity)”. This emphasis on 'brevity' extends to the introduction to the Holy Creed, directing that “if” there are Catechumens the traditional exclamation, “The Doors! The Doors!” is to be used, but otherwise omitted. The problem here is that it is debatable whether the “The Doors! The Doors!” ever related to the catechumens, given that they presumably were dismissed earlier, before the Great Entrance. Rather the exclamation was a warning to ensure that non-Christians not be admitted to the celebration of the Eucharist and Holy Communion. Thus, the exclamation has traditionally served as a reminder to worshippers of times of past persecution and the superlative holiness of the liturgical actions that will follow.

As to the omission of the Litany of the Catechumens and editing of the two Litanies of the Faithful "for brevity", the time factor in their inclusion amounts to a mere two or three minutes. Also, one must consider the spiritual possibility that whether present or not, the Church should always offer prayers for catechumens, recognizing that there are perhaps many whom our Lord is leading to His Church who have yet to realize this and so have not yet participated in the Divine Services. Offering this litany confirms our prayers to strengthen those 'invisible catechumens' whom we may not even know but whom God will lead to join with us in the future. It also reminds us of our duty to proclaim the Gospel in our whole life, not just in church, and thus encourages us to give daily witness to the True Faith such that those invisible catechumens may be inspired to come forward. Reflecting on the call to evangelism, omitting the Litany of the Catechumens could be said to border on sacrilege.

When viewed together, it seems that the various optional directions in the Final Draft combine to promote a Liturgy significantly influenced by the current Roman Rite Mass. While a few of the options present legitimate variations in the customary practice of the Church, most have the effect of encouraging a ‘shortening’ of the Liturgy to suit modern sensibilities and convenience or to promote a more "people friendly" (to wit, emotionally moving rather than spiritually uplifting) experience. During the reception of Holy Communion by the laity, there is even a note allowing the singing of “spiritual hymns” after the singing of “Receive me now, O Son of God”. One shudders at the thought of chanters or a choir singing “And He Will Lift You Up on Eagles Wings” at this most sacred moment!

This brings us to the final issue to be addressed in critiquing the Final Draft – the Melkite translation of the hymnody of the Church in general. The Melkites are to be congratulated for being among the first to produce handy, relatively inexpensive editions of almost the entire Byzantine hymnological corpus. The Octoechos, Menaion, Triodion, etc. have all been published, with nearly each now being in a second edition that has corrected and expanded the material contained therein. In fact, a volume for Holy Week and the General Menaion, are the only books still needing to be published.

The only objections to these important and essential volumes are the absence of sturdy hardbound editions of sufficient quality for long term use at the Psalterion and the rather pedestrian language used throughout. As I am not familiar with the text of these books in Arabic, I can only note that in comparison to the Greek, and translations based directly on the Greek, most of the troparia and stichera in the Melkite hymn books read as sufficient paraphrases, albeit devoid of the poetic elegance found in many other translations. That said, these books do present the material in serviceable English and the translators and hierarchy authorizing them are to be highly commended!

In conclusion, the Final Draft of the Melkite Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom is a usable but flawed project. As a volume intended for direct use in the worship of the Church it is neither fish nor fowl, neither presenting exact rubrical information for the clergy nor clear easy to follow formatting for the laity. One could make the case that once finalized, the volume could form the basis for specifically designed editions prepared for the clergy, the laity, and chanters/choir usage although some comment has been made that this is not planned.

In its current format the Final Draft is impractical and certainly not recommended for someone attending Melkite Divine Services for the first time. One can only hope that the hierarchy of the English-speaking Eparchies will reconsider some of the decisions that have led to the current edition, both in terms of layout, rubrics/descriptions and translation choices, and go one more round before considering the project finished. A bit of extra time and work now would undoubtedly result in a much more refined product with long-lasting potential.

One final suggestion would be that where commonly recognized English texts have been used in Byzantine churches (Catholic or Orthodox) for generations, consideration could be made to utilize these or else model specific Melkite texts on them, instead of presuming the necessity of a unique translation in every instance.

Our thanks to the translators, editors, and all others who have dedicated so much time, effort, and prayer to this project. These considerations are made not to criticize individuals but, God willing, to inspire the Melkite Church to even greater work on this most important project. The future sustainability and growth of the Melkite Church outside the Middle East depends entirely on such God-pleasing work and the recognition that Antiochian Christianity must be allowed to embrace all people, regardless of their ethnic heritage, with equal openness to that offered by the Roman Church. As with recent directives and clarification of intentions from the Holy See for translations of the Roman Rite, Churches of the Byzantine Tradition, regardless of the intermediary historic origins, need to start fresh from the Greek in seeking to produce vernacular translations, making reference to the ethnic 'intermediary' language as necessary. To do otherwise will only result in more inadequate translations and the generational loss of members who neither maintain fluency with the "original" ethnic language nor are given the opportunity to encounter the purity and majesty of the original Greek.

From the beginning, our little community has participated in the trial use of the several editions of the Common Language Translation project for English-speaking Melkites. With each new released edition, we have taken full advantage of the options permitted and tried them all out at least once. Ultimately, we have returned to the traditional 'options' and practices that have proven themselves efficacious for all Byzantine Rite Christians following the Typikon of the Great Church. That said, a review of the project's "Final Draft" is in order.

THE FINAL DRAFT AND PROCESS OF ESTABLISHING A COMMON ENGLISH TRANSLATION FOR ALL BYZANTINE RITE CHRISTIANS

The goal of a common text of the Divine Liturgy for English-speaking members of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church is a laudable one. A tragedy for the development of Byzantine Christianity in the Americas and other English-speaking regions has been the history of ad hoc translating, with both Catholic and Orthodox jurisdictions acting independently, and some jurisdictions producing various efforts of individuals having no coordination or support from the hierarchy. It is not uncommon to find that one jurisdiction may have two, five or more ‘approved’ (or commonly employed) translations each featuring twists of phrasing, anomalies and idiosyncrasies. This discordant reality makes a visit to another parish of ones own jurisdiction an adventure in attempting to avoid stumbling over linguistic variations not encountered in ones own parish. Compound this with the number of translations produced by ‘other’ jurisdictions and the frustration and confusion of the laity across the board becomes easily appreciated.

The fact that English is one of the few modern languages experiencing this frustrating, and spiritually stunting, situation is understandable given the historic context of the waves of distinct immigrations to the “New World”. The various small pockets of individual Eastern Christian communities were typically viewed by their “Old World” hierarchy as living in diasporas. Thus, they were encouraged to continue using the old language versions of the Divine Services and prayers rather than to produce English editions for the generations that would follow. Thus, while other linguistic nations moved to produce suitable translations in the new language, many of which have become the standard used by all Byzantine tradition Christians speaking said language, one may literally fill a bookcase with the numerous English editions of the Divine Liturgy produced by various Orthodox and Catholic jurisdictions over the years, each featuring their own merits and deficits, their own inspiring turns of phrase, their own clumsy or downright incomprehensible translations.

Given this historic context, the new Common English Language translation project by the Melkites is laudable in its intentions. One could take from the very fact of the project a hope that once finalized the resulting product might provide the springboard for the production of a common English translation for all Byzantine Rite Catholics. Indeed, one could dream of the day in which such efforts would lead to a definitive English edition that all Byzantine Christians, Orthodox and Catholic, could agree on for their jurisdictions’ regular worship.

Accepting the wholesomeness of the goal to produce a standard edition of the Divine Liturgy for English-speaking Melkites, it is in order to consider the results of the efforts made thus far. This is particularly important now as the currently released edition is proclaimed the “final draft”. Therefore a careful review of the draft’s accuracy of text, rubrics, and format deserves serious review. In addition, and more importantly, the quality of the English text that is being promulgated needs very careful consideration.

THE FINAL DRAFT – ITS GOALS, LIMITATIONS ON THE PROJECT AND RESULTANT TRANSLATION ISSUES

For the US edition of the Final Draft, the Eparch has provided an “Instruction” that serves as a general introduction as well as explanation for the selection of several particular translation choices. The Instruction notes that the English translation is the result of a process that began with the “the official Greek text”, followed by “the official Arabic translation as approved by the Melkite Holy Synod in 2005". The English translation is portrayed as the next step in the process of bringing to the vernacular the fruits of the Apostolic Tradition embodied in the original texts.

Emphasis immediately must be given to the fact that the translators were required to produce an English translation that conformed to the Arabic in all particulars rather than the “official Greek text”. The significance for this is understandable, but ultimately controversial. In terms of the particular customs and idiosyncrasies of the Melkite usage, it is natural that following the Arabic texts approved by the Holy Synod is a commendable choice. However, for the text of the Liturgy itself, such an approach is problematic; the English Final Draft is a translation of a translation. This is the very criticism of such English language Bible translations as the Douay, the Confraternity Edition, and the original translation of the Jerusalem Bible. While not condemnatory in and of itself, such an approach should always be guided by reference to the original text, and where peculiarities or questions arise weight be properly given to the original. (Note that this approach would actually strengthen the argument for reliance on the Septuagint as the basis for English translations of the Old Testament rather than relying on Hebrew, and in particular the Masoretic text.) There are nuances in every word and turn of phrase in any language that when employed can convey more accurately the originals meaning in translation; but if the translation is used as the authorized text for translation into a third language the resulting phrasing may be completely misleading.

The quintessential example of this is in the case of the Final Draft is the choice to use “now and always and forever and ever” versus the traditional English rendering “now and ever and to the ages of ages”. The stated justification for this choice in the Instruction is “that every major modern translation of these words in Scripture…employs the former, forever and ever.” One could be forgiven for viewing this choice as trivial. However, the original Greek Scriptures, the Divine Services and various commentaries of the Church Fathers use the term translated “ages” with specific import and meaning. In Greek the phrase “now and ever” or “now and always” already conveys the sense of “forever” before including the phrase “ages of ages”.

The term “age” in Greek has specific connotations indicating more than the simple measuring of time, and to render the phrase as “for ever and ever” is as potentially misleading as assuming that “era” carries no significant distinction than, say, “recent years”. (Please note that “forever” is specifically and consistently rendered “for ever” in the Revised Standard Version hinting at the distinction of “unto ages” versus “forever” in the original Greek.) “To the ages of ages” indicates not just an endless passage of time, but the taking into account of every age, era and circumstance. It clarifies the glory due to God as possessing a fullness that extends beyond all created realities. Thus, the selection of “for ever and ever” subtracts from translational accuracy and weakens the theological import of the original Greek.

Similarly, the substitution of “forgive me” for the expression “be propitious to me” is justified in the “Instruction” as being “clear and accessible in conveying the same meaning”. In fact, this simply is not so. The term propitious implies kindness, mercy and a favorable disposition. Thus, traditional (commonly chosen) English translations have utilized phrases such as “have mercy on me and forgive me” or “be propitious to me and forgive me”. The simplification (reduction) of the phrase to “forgive me” alone removes the dialogic framework of the prayer, actually omits the reference to God’s great mercy, and thereby ignores the very reason one can ask to be forgiven. This is at best a deficient paraphrase and at worst a gross lack of fidelity to the original.

Other examples of poor translation can be seen in the hymn to the Theotokos “It is truly right”. The translation’s text betrays an inferior understanding of the Incarnation by choosing “you gave birth to God the word in virginity” versus the more accurate translation “without corruption you gave birth to God the Word”. The word “corruption” is an exact translation of the Greek, which does not refer to sexual intercourse but rather the general corruption of human nature. It therefore conveys the truth that the Virgin conceived and gave birth to our Lord without the corruption of ancestral sin.

It must also be noted that the translation ends: “You are truly Theotokos, you do we exalt.” Given that in context the English word “magnify” is a direct translation of the Greek and, indeed, one may argue a cognate term, the justification for using “exalt” can only be that it happens to be the inferior term used by Baron De Vinck and Archbishop Raya (of blessed memory) in their original translations over a half century ago.

THE FINAL DRAFT AND INJUDICIOUS TRANSLATION DECISIONS

These examples demonstrate the principle difficulty with the translation. The translators were apparently restricted to conform their work to a translation (Arabic) of the original (Greek) instead of working directly from that original. To this was coupled the problem that the project freely borrows from pre-existing English-speaking Melkites translations. These prior works produced by translators for whom English was not their primary language, often employ awkward phraseology. These two facts combine to weaken the translation in many ways.

For example, a typical Ekphonesis (doxological conclusion to a prayer) in the Final Draft reads, “That being ever protected by Your power we may render glory to You, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, now and always and forever and ever.” The issue here is the absence of prepositions and articles for “Father, Son and Holy Spirit.” In Greek, “to the” is clearly implied by the repetition of the conjunction “and”. An exact word for word translation of the phrase from Greek would be “to (the) Father and (to the) Son and (to the) Holy Spirit…” The Greek nouns used in such a construction clearly indicate a comprehension that 'reads' “to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit”. The inflected form of the nouns carries the prepositional connection with it.

It begs the question to ask why the option to translate Trinitarian references using fuller, more majestic phrasing was passed over. One can only assume that to one for whom English is a second or third language the nuanced differences in English syntactical construction went unnoticed. However, the lack of the full prepositional phrases in the conjunction weakens the Trinitarian emphasis inherent in the original Greek. As translated in the Final Draft the Trinitarian reference could too easily be misinterpreted as modalistic rather than hypostatic.

Again, the problem originates in the directive to produce a text that mirrored the Arabic as exactly as possible. It seems that the majority of the editors, having English as a second or third language, misunderstood the impact of narrowing of the phrase would threaten to have on weakening the Trinitarian reference for the English worshipper and opted to approve a phrasing that mirrors the ‘letter’ of the source but diminishes theological nuance in the product. In the Final Draft’s phrasing of almost all Ekphoneses, the Persons of the Trinity grammatically become almost an afterthought. A more thorough acquaintance with English would have avoided this. A more careful adherence to the original Greek would have necessarily precluded it altogether.

The fault is in the directive to work from the Arabic instead of the Greek. A more rational approach would have been to translate from the Greek and compare the results with the Arabic. This would have undoubtedly produced a more accurate work in English while allowing for reasonable conformity with the Arabic.

RUBRICS, OPTIONS AND FORMATS

One distinctive problem with the released edition of the Final Draft is absence of rubrics. By definition, rubrics provide clear explanation of the movements and actions accompanying the text of the ritual. Unfortunately, the Final Draft provides vague descriptions of the teleturgical action that in no way promote basic conformity amongst the English-speaking clergy. The aim seems to have been to provide the laity with a basic understanding of what the clergy are doing during at any particular moment in the Liturgy. However, as with earlier drafts, the officially released volume is organized like a study text. The liturgical flow is repeatedly interrupted by ‘rubrics’ that diverge to note various options requiring the worshipper to anticipate which option a particular community follows and know how far to skip ahead to keep up with the given celebration. While earlier drafts at least occasionally noted the options and place more detailed information at the end of the volume, the Final Draft seeks to provide information about various optional practices in great detail at the exact point in the text of the liturgy wherein they occur. The result is an extremely unfriendly user’s edition. (A side note: As no discussion has yet been formalized concerning a ‘definitive’ translation of the Divine Liturgy of St Basil the Great, it is curious that several prayers from that Liturgy are included in the work under consideration.)

Amongst the various options allowed for the antiphons after the open litanies, the Final Draft does allow the Beatitudes along with the basic stichera from the Octoechos. This is extremely welcome as it allows the laity to experience more of the rich hymnody of the Church, with perhaps a goal of encouraging more participation in the offering of Great Vespers, Orthros or other Divine Services that sadly tend to be forgotten in many Melkite communities today. It must be noted, however, that for a project that intends to unite the English-speaking Melkites in using one text with specifically delineated options, it is somewhat ironic that at the end of the Beatitudes in each Tone the text includes two separate translations of its Troparion of the Resurrection. Obviously no consensus has been reached on a standard text for these commonly used troparia.

This also brings to the fore the question of the legitimacy of some of the options themselves. Here and there options are presented that obviously reflect the spirit of the Roman Church's post-Vatican II ‘people’s participation’. For example, the Ektene after the homily presents an option in which ‘readers’ chosen from the laity stand in the “middle aisle” facing each other and offer petitions from a large collection at the end of the volume. (The text is silent whether additional ‘made up’ petitions are allowed.) In short, a practice is being introduced that is a direct copy of the Roman Novus Ordo practice of "general intercessions" after the homily – a practice that is, to my knowledge, without precedent in the Byzantine Tradition.

The directions for the litanies after the homily also are troublesome from a theological perspective. The Litany of the Catechumens is directed to be done only “if there are Catechumens” present, and only one of the Prayers of the Faithful is to be included “(for brevity)”. This emphasis on 'brevity' extends to the introduction to the Holy Creed, directing that “if” there are Catechumens the traditional exclamation, “The Doors! The Doors!” is to be used, but otherwise omitted. The problem here is that it is debatable whether the “The Doors! The Doors!” ever related to the catechumens, given that they presumably were dismissed earlier, before the Great Entrance. Rather the exclamation was a warning to ensure that non-Christians not be admitted to the celebration of the Eucharist and Holy Communion. Thus, the exclamation has traditionally served as a reminder to worshippers of times of past persecution and the superlative holiness of the liturgical actions that will follow.

As to the omission of the Litany of the Catechumens and editing of the two Litanies of the Faithful "for brevity", the time factor in their inclusion amounts to a mere two or three minutes. Also, one must consider the spiritual possibility that whether present or not, the Church should always offer prayers for catechumens, recognizing that there are perhaps many whom our Lord is leading to His Church who have yet to realize this and so have not yet participated in the Divine Services. Offering this litany confirms our prayers to strengthen those 'invisible catechumens' whom we may not even know but whom God will lead to join with us in the future. It also reminds us of our duty to proclaim the Gospel in our whole life, not just in church, and thus encourages us to give daily witness to the True Faith such that those invisible catechumens may be inspired to come forward. Reflecting on the call to evangelism, omitting the Litany of the Catechumens could be said to border on sacrilege.

When viewed together, it seems that the various optional directions in the Final Draft combine to promote a Liturgy significantly influenced by the current Roman Rite Mass. While a few of the options present legitimate variations in the customary practice of the Church, most have the effect of encouraging a ‘shortening’ of the Liturgy to suit modern sensibilities and convenience or to promote a more "people friendly" (to wit, emotionally moving rather than spiritually uplifting) experience. During the reception of Holy Communion by the laity, there is even a note allowing the singing of “spiritual hymns” after the singing of “Receive me now, O Son of God”. One shudders at the thought of chanters or a choir singing “And He Will Lift You Up on Eagles Wings” at this most sacred moment!

This brings us to the final issue to be addressed in critiquing the Final Draft – the Melkite translation of the hymnody of the Church in general. The Melkites are to be congratulated for being among the first to produce handy, relatively inexpensive editions of almost the entire Byzantine hymnological corpus. The Octoechos, Menaion, Triodion, etc. have all been published, with nearly each now being in a second edition that has corrected and expanded the material contained therein. In fact, a volume for Holy Week and the General Menaion, are the only books still needing to be published.

The only objections to these important and essential volumes are the absence of sturdy hardbound editions of sufficient quality for long term use at the Psalterion and the rather pedestrian language used throughout. As I am not familiar with the text of these books in Arabic, I can only note that in comparison to the Greek, and translations based directly on the Greek, most of the troparia and stichera in the Melkite hymn books read as sufficient paraphrases, albeit devoid of the poetic elegance found in many other translations. That said, these books do present the material in serviceable English and the translators and hierarchy authorizing them are to be highly commended!

In conclusion, the Final Draft of the Melkite Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom is a usable but flawed project. As a volume intended for direct use in the worship of the Church it is neither fish nor fowl, neither presenting exact rubrical information for the clergy nor clear easy to follow formatting for the laity. One could make the case that once finalized, the volume could form the basis for specifically designed editions prepared for the clergy, the laity, and chanters/choir usage although some comment has been made that this is not planned.

In its current format the Final Draft is impractical and certainly not recommended for someone attending Melkite Divine Services for the first time. One can only hope that the hierarchy of the English-speaking Eparchies will reconsider some of the decisions that have led to the current edition, both in terms of layout, rubrics/descriptions and translation choices, and go one more round before considering the project finished. A bit of extra time and work now would undoubtedly result in a much more refined product with long-lasting potential.

One final suggestion would be that where commonly recognized English texts have been used in Byzantine churches (Catholic or Orthodox) for generations, consideration could be made to utilize these or else model specific Melkite texts on them, instead of presuming the necessity of a unique translation in every instance.

Our thanks to the translators, editors, and all others who have dedicated so much time, effort, and prayer to this project. These considerations are made not to criticize individuals but, God willing, to inspire the Melkite Church to even greater work on this most important project. The future sustainability and growth of the Melkite Church outside the Middle East depends entirely on such God-pleasing work and the recognition that Antiochian Christianity must be allowed to embrace all people, regardless of their ethnic heritage, with equal openness to that offered by the Roman Church. As with recent directives and clarification of intentions from the Holy See for translations of the Roman Rite, Churches of the Byzantine Tradition, regardless of the intermediary historic origins, need to start fresh from the Greek in seeking to produce vernacular translations, making reference to the ethnic 'intermediary' language as necessary. To do otherwise will only result in more inadequate translations and the generational loss of members who neither maintain fluency with the "original" ethnic language nor are given the opportunity to encounter the purity and majesty of the original Greek.

Labels:

Divine Liturgy,

Eastern Churches,

spirituality,

translations

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)